Free at last. But what took so long?

- Justine Barron

- Sep 20, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 21, 2022

As Marilyn Mosby vacates Adnan Syed's conviction before leaving office, it's a good time to ask questions and to recall Thiru Vignarajah's involvement in the case.

Adnan Syed is free. By law, he is no longer guilty of murdering his close friend and one-time girlfriend Hae Min Lee in 1999 in Maryland. It is good news for many listeners of Serial Podcast, which, in 2014, suggested his possible innocence. (The podcast also devoted an entire episode to the question of whether or not he could be a psychopath.) The first season of Undisclosed Podcast addressed the facts of the case better than Serial: bodily lividity, witness coercion, the school schedule, unreliable cell data, the growth of grass under cars, and more—evidence that upended the police narrative presented in Serial.

On September 15, 2022, the Baltimore state's attorney's office (SAO), under Marilyn Mosby, filed a motion to vacate Syed's conviction. It referred to some known issues with the case, which previously came up during years of hearings and appeals. It also discussed new evidence: police knew about and overlooked two compelling suspects, one of which "threatened to kill Lee." One was a serial killer. (Undisclosed did discuss a serial killer.) The motion wasn't altogether explicit about the two suspects, only that they were known.

Assistant State's Attorney Becky Feldman, who oversees "sentencing review" at SAO, wrote that this evidence was never turned over to the defense, in violation of the rules of Brady v. Maryland. The evidence came up during a "nearly year-long" investigation by the defense and SAO, she wrote.

Some questions: What took so long? And who didn't turn this evidence over to the defense? One party? Multiple parties, over years? There have been prosecutors working this case for more than twenty years, at the city and state levels. Did all of them keep this information buried?

According to reporters, Feldman gave an outline of when she learned about the new information in court. She claimed her office had been investigating the case for about a year, since October 2021, but she didn't obtain the "case file" until June 2022. What case file? What was she investigating before? Feldman started in the Sentencing Review Unit at SAO in December 2020. How did this new information suddenly emerge and from where exactly? Syed deserves answers.

Mosby, Syed, and Thiru Vignarajah

It is generally thought that Thiru Vignarajah—former federal and state prosecutor and frequent candidate for office—handled the appeals in the Adnan Syed case for the office of the attorney general (OAG). That is only part of the story of his involvement in this case.

Incidentally (or not), Vignarajah and his sister went to the same high school as Syed and Lee—Woodlawn High, west of Baltimore—just a few years ahead of them.

Anyway, the story of Vignarajah's involvement in the Syed case is not a typical story of a state prosecutor handling appeals. The story starts in January 2015, when Brian Frosh took office as the Attorney General of Maryland. He hired Vignarajah as one of his two deputies. Serial was already a global phenomenon. Right away, Frosh's office began handling appellate issues in the case. Syed's team had lost an application for post-conviction relief (PCR) and was appealing. An Assistant Attorney General, Edward Kelley, seemed to be handling the case, but Vignarajah's name was quickly added to motions.

In the summer of 2015, the Court of Special Appeals (COSA) decided to remand the case back to the Baltimore City Circuit Court. As such, it should have returned to Mosby's office, which had the case originally. SAO handles cases in Baltimore circuit court; OAG handles appeals before state courts. Before Mosby took office, SAO handled Syed's previous PCR proceedings in circuit court. So, in 2015, Mosby's office had its first chance to review the case and determine if it wanted to oppose Syed's request for a new trial.

That didn't happen. Vignarajah stayed on the case. He argued the case in a February 2016 PCR hearing before the circuit court, opposing the request. The hearing garnered international attention from the media.

According to legal sources, it is unusual for a prosecutor from the state Attorney General's office—let alone one of two new deputies, overseeing the entire department—to handle a PCR hearing in circuit court at the city level. Sources from OAG (interviewed for a previous article) describe Vignarajah as zealous around both the Syed prosecution and his own political fortunes.

More questions: How and why did the Syed case stay with OAG and Vignarajah? What kinds of conversations did SAO have with OAG and/or Vignarajah about the case? Why didn't SAO hold onto its case under Mosby?

Mosby's administration was also new in January 2015. While Vignarajah was handling the PCR, her office was in the middle of the trials of six officers in Freddie Gray's death. Just as Vignarajah, a new deputy—the number two in his office—was personally prosecuting the Syed case, so too Mosby's second and third in command were personally prosecuting the Gray cases in court. (There's a whole other article I could write about deputies prosecuting high profile cases in court during 2015-6, instead of delegating.)

In any case, Syed won the highly publicized PCR in 2016 and was awarded a new trial in Baltimore Circuit Court. Enough evidence was presented for the judge to determine that the original case wasn't solid. This was another point at which SAO, under Mosby, could have reconsidered its prosecution and dropped the charges. Instead, Vignarajah filed a request to appeal the judge's finding, which the Court of Special Appeals allowed. He put a hold on Syed's new trial.

While this was happening, Vignarajah was asked to leave OAG, as I recently reported. There was the Project Veritas scandal and an internal investigation concerning his treatment of staff. This wasn't known at the time. Publicly, OAG allowed him to say he was choosing to leave. (OAG hasn't confirmed or denied the story. Neither has Vignarajah, but the Baltimore Sun later confirmed the story.)

Vignarajah left OAG but he didn't leave the Syed case. He joined DLA Piper law firm as a partner and, during 2017-8, continued to oversee the Syed prosecution, pro bono. OAG named him a "Special Assistant Attorney General." He handled the appeal of Syed's PCR victory.

This was now Vignarajah's third unusual involvement in the Syed case, according to legal sources. Special prosecutors do exist, but this was a rare set of circumstances. Why was this disgraced former prosecutor not only allowed to try the case in court but, it seems, given the power to drive the state's agenda around it? Vignarajah is the only attorney named on most of the motions, besides Frosh.

While handling the Syed appeal, Vignarajah decided to run for office in 2018. He opposed Mosby in her reelection for state's attorney. Ivan Bates was also a candidate. For some observers, Vignarajah functioned as a "spoiler" in the race. If he hadn't run, Bates could have perhaps defeated Mosby, they claim. Instead, Mosby won.

The Syed case came up during the election. Bates promised to drop the charges if elected, based on the evidence presented during the PCR hearings. Mosby refused to take a position on the case. It was still within her office's power to reconsider the case and vacate the conviction, but she had effectively handed it over to Vignarajah, her now opponent.

That same year, the Court of Special Appeals upheld Syed's request for a new trial, yet another chance for Mosby to reconsider this ongoing prosecution. It was a temporary victory. Vignarajah continued his aggressive fight, filed additional motions and appeals, and ultimately, in March 2019, was victorious. The Court of Appeals denied Syed's new trial. Two years after winning a new trial—and one year after winning it again—Syed lost his chance at freedom. Later that year, the Supreme Court denied his last pitch for a new trial.

Cut ahead to June 2022. the same three candidates are running for state's attorney again. Vignarajah, who just lost the Baltimore mayoral election in 2020, is endorsed by Judge Wanda Heard. Numerous media outlets report on the endorsement while failing to mention that Heard was the judge who handled the original Syed trial. That is, Vignarajah was fighting to uphold the conviction that happened in her courtroom. Heard had refused a new trial for Syed in 2000. This was an endorsement with a notable history.

Anyway, that brings us back to the events surrounding Syed's recently vacated conviction. Just before the July 2022 election for state's attorney, ASA Feldman reportedly sees a file—or something—that contributes to her belief that there is evidence to vacate Syed's conviction. SAO announces the findings three months later, after the election.

Some people have pointed out that Mosby timed this announcement to coincide exactly with her own trial, which seems obvious. She is facing federal charges for financial fraud, and that case kicked off in court just as her office made the Syed announcement. The Syed story distracts from the bad news around her.

Yet, as long as we are speculating about timing, there's also the timing of the election. For more than seven years, Mosby never made one public statement about the Syed case or used her powers to help free him. She allowed Vignarajah to handle the case. She didn't step in to help Syed until after both she and Vignarajah lost their election. She finally acted when it no longer affected Vignarajah.

Vignarajah isn't mentioned in any of yesterday's news reports about Syed's freedom, but he is still a part of the story. Consider the statement Frosh gave in response to Mosby's motion to vacate:

![Statement by Attorney General Frosh Following Press Conference By State's Attorney Marilyn Mosby.... "Among the other serious problems with the motion to vacate, the allegations related to Brady violations are incorrect. Neither... Mosby nor anyone from her office bothered to consult with either the [ASA] who prosecuted the case or with anyone in my office.... The file... was made available on several occasions to the defense.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/e26bd0_a829b4ef5bd248e6b00e40754b90578a~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_843,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/e26bd0_a829b4ef5bd248e6b00e40754b90578a~mv2.png)

Frosh gave a cryptic statement, but it reveals a little. He denies that his office committed Brady violations while at the same time acknowledging that the accusation was being levied at his office.

Susan Simpson, who investigated the case for Undisclosed Podcast and assisted with Syed's defense, disputed Frosh's statement:

All of these statements and the news reporting are in the passive voice. Someone is being accused of a serious Brady violation. Who? Who knew about the evidence, and who withheld it from the defense? Was it someone from SAO originally? Was it Vignarajah when he took over the prosecution? Was it both? And who restored it to the case file? When did that happen?

Incidentally (or not), Vignarajah has a history around Brady violations. In 2015, he was accused of a serious violation after convicting David Hunter for the murder of Henry Mills, a case that got him a ton of positive press. Defense attorneys accused Vignarajah of withholding evidence of another suspect from the defense. In fact, two police officers testified that they had told Vignarajah directly about the other suspect, but he never shared that information with the defense.

Note: A very resourceful website, adnansydwiki.com, outlines every filing and hearing in the case and informed this article. It is not without bias, but it has links to the original documents. It has interesting information about Vignarajah missing deadlines, making mistakes in filings, and using the Baltimore Sun's Justin Fenton to get filings quickly into the press.

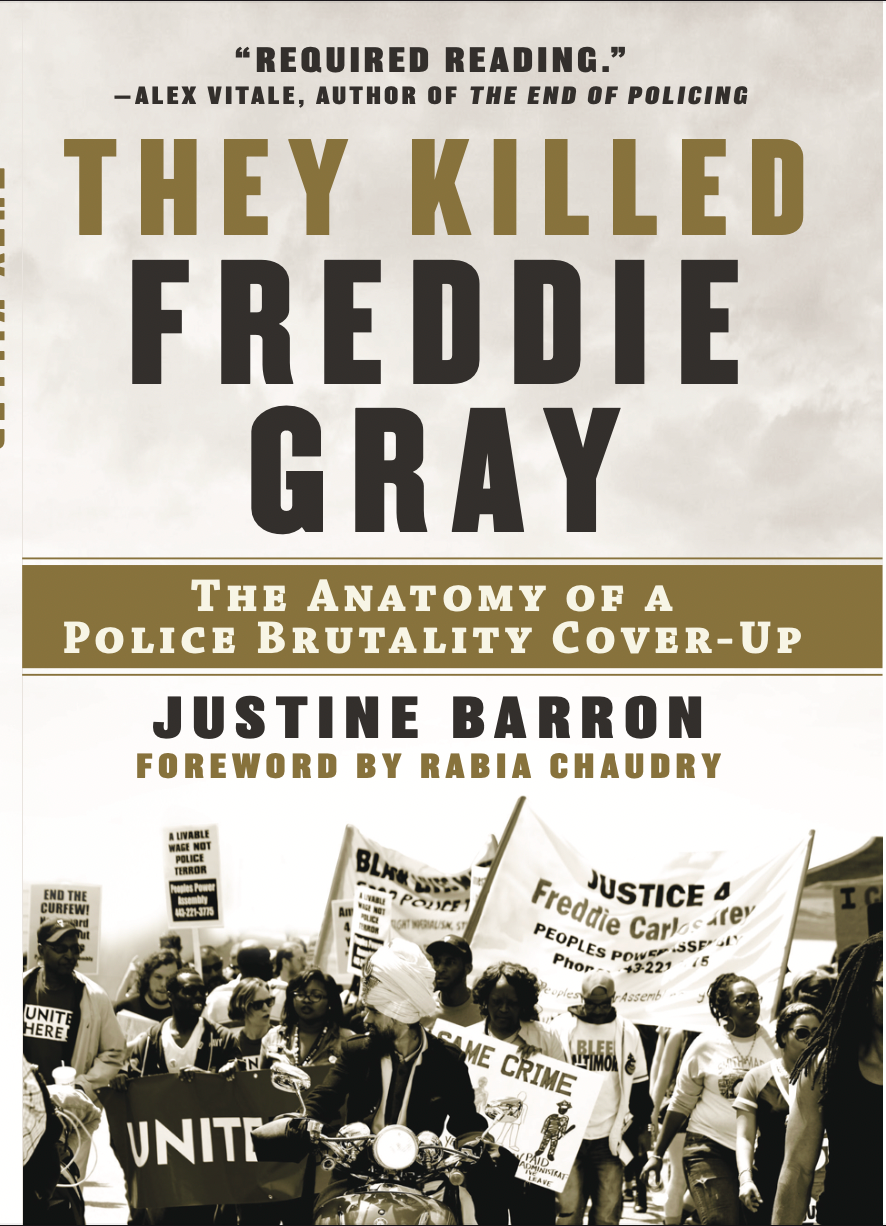

For more on Mosby and the Freddie Gray case, you can pre-order my upcoming investigative book.

This is a great summation of the evolution of the case in the past decade or so. I just re-watched the HBO documentary series. Thiru makes a couple appearances but they are not favorable. I read most of the local stories over the past couple of days and did not see nary a mention of Thiru. You ask fascinating questions - all unanswered and unasked by local reporters. Thank for reporting this and for all of your work.